The Times Square Taoist master who changed my life

The most unlikely place became the gateway to the life I never knew I needed.

This is the fourth article in a series chronicling my 30-year meditation journey. Missed the beginning? Start here with Part 1, or read Part 2 here, and Part 3 here.

Burnout and arrival

By the time I landed in New York City in 2008, I was absolutely fried.

I’d just spent years working a job that had me on the road nearly eight months out of the year, bouncing between continents, producing glossy investment and tourism reports.

The kind of work that looks wildly impressive from the outside: suits, photo ops with presidents and CEOs, lavish events, a passport fat with stamps. I’d checked every external box of success.

And yet, beneath it all, I was burnt out, unrooted, and low-key panicking about what the hell to do next with my life.

So I made a decision: if I was going to hit pause, it had to be in New York.

It’s where cosmopolitan misfits go when they’re too world-traveled and too soul-spun to land anywhere else. I scraped together what savings I had, paid an expensive immigration/PR agency to help me secure a special talent visa (thanks to all those photos with dignitaries), and declared—without a plan—that I’d start over in the city that never sleeps.

What I didn’t know then was that the most important move I’d make in New York wouldn’t be professional at all.

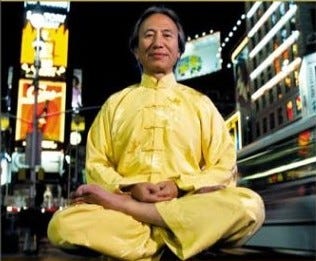

It would be stepping into a modest studio tucked into 156 W 44th St—pretty much smack in the middle of Times Square—to study with a quiet Daoist master named C.K. Chu.

Following the thread

I’d first heard about Chu years earlier through Jim Borrelli, a teacher I met while taking a break in Los Angeles. Jim introduced me to nei kung—a stripped-down, no-fluff internal art that he learned from Chu and was among the very few certified by him to teach it.

That session was unforgettable: part martial stance, part furnace of stillness, and all presence. Jim credited nei kung for his mental clarity and creative stamina, and he often spoke of Chu with the reverence one reserves for a true master. You can read about that encounter in Part 3 of this series: Cockblocked but Enlightened.

So when I arrived in New York, completely lost and unsure what came next, I remembered that thread—and followed it to the source.

I had tried to find solace in every cozy spiritual corner the city had to offer. I lost track of how many silent New Age shops I wandered into around the East and West Village. I spent hours circling Central Park and every pocket of greenery Manhattan could offer in an effort to elicit some sort of Woody-Allenesque life-changing insight.

But ironically, it wasn’t in the quiet enclaves where I found peace. It was in the chaos of Times Square—one of the most hectic places on earth—where real stillness finally found me.

I didn’t have language for it then, but what I was really doing was taking the first step into what would become what I now affectionately call my “year of nothing”—a full sabbatical year that completely changed my life.

Because yes, this encounter with Chu was the catalyst. The moment I stopped forcing. I stopped chasing. That I learned to sit down and actually feel what the f*ck was happening inside me.

That year changed everything.

I didn’t stay in New York. I ended up in Buenos Aires. Met the woman who would become my wife. Became a father—something I’d never imagined or wanted. My life flipped upside down.

And yet it wasn’t chaos. It was the first time in years I’d actually been living. Recalibrated in body, mind, and soul.

That transformation didn’t start with a vision board.

A different kind of studio

I still remember my first time walking into Chu’s Times Square studio. What struck me immediately was the contrast—the space had none of the polished branding or performative serenity I’d seen in so many yoga studios scattered across the Village.

Those spots always seemed to be trying a little too hard: curated candles, overpriced herbal tinctures, and instructors who spoke like they were auditioning for a wellness TED Talk.

Chu’s place was the opposite. Austere. Almost monastic. A wooden floor. Sparse walls. The vibe was closer to a kung fu dojo than a yoga retreat—and that’s exactly what made it feel real.

There was a small metal stand near the entrance with a basic kettle and some tea bags. Nothing fancy. Just enough to offer a gesture of welcome. That’s it. And yet, the space hummed with something I didn’t feel anywhere else: humility. Raw grit. Presence.

What made it even more fascinating was the quiet dissonance I spotted on one of the walls: a collage of photos featuring Chu standing next to celebrities. I distinctly remember one of him with Jackie Chan.

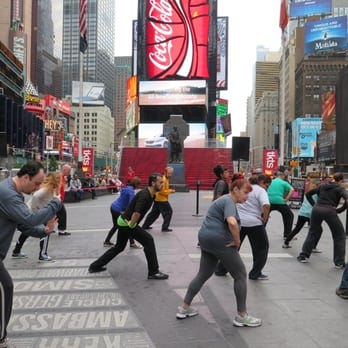

I later learned he regularly taught open-air Tai Chi classes right in the middle of Times Square. Those classes were famous enough to be a bit of a tourist attraction. I regret never attending one of them.

Turns out, this unassuming man in loose-fitting clothes, who moved like water and spoke sparingly, had quietly become one of the first pioneers to bring Tai Chi, Nei Kung, and Taoist meditation to the U.S. in the 1970s.

He was an eminence in internal martial arts circles. But you’d never guess it from the way he carried himself. He looked like someone you might miss entirely in the subway. And that was part of the magic.

I signed up immediately. Chu didn’t teach every day, but when I found out he was holding a series of Nei Kung workshops, I cleared my schedule and enrolled in all of them.

For the next three months—whenever I was in New York—I showed up. I trained in Nei Kung, dabbled in Tai Chi (which I admired but never quite connected with), and joined quite a few of his Taoist meditation sessions.

Practice and presence

Both Nei Kung and Taoist meditation stuck. Nei Kung's stripped-down simplicity and raw physicality just resonated. During the Nei Kung sessions, his instructions were minimal—"Body concave," "Pelvis tucked," "Knee over toe"—but his corrections were surgical.

When he touched you to adjust a stance, it was like being nudged by a tuning fork. He was tiny, but radiated real power. Sometimes he’d give you a quick shove just to prove a point—always with a dry, warm little laugh that cut through your self-seriousness like sunlight.

He moved like Wu Wei in motion. Pure effortless action. You didn’t need to read a single Taoist text to understand it. You just had to watch him walk across the room.

And those meditation workshops? That’s where I got closest to Chu himself. We’d sit in a circle, and he would guide us through the breathing, the postures, the alignment of body and spirit.

The technique was deceptively simple: sit upright, spine straight, with your attention focused in the lower belly—the dan tien. The breath, natural and unforced, would settle there, anchoring you. There were no mantras, no elaborate visualizations, no “love and light” affirmations. Just stillness. Presence. Simplicity.

It was minimalist in the truest sense. Taoist meditation didn’t ask me to improve myself. It didn’t urge me to transcend or reprogram my thoughts. It didn’t even require me to be kind.

It just asked me to sit.

And in that raw, stripped-down silence, I found something more profound than in any technique I’d tried before.

Compared to mindfulness meditation—as I had practiced it after reading Kabat-Zinn—it felt less like managing the mind and more like letting go of the need to manage anything at all. Mindfulness taught me to observe. Chu’s method taught me to dissolve.

Minimalist. Grounded. Warrior stillness.

The kind that doesn’t announce itself, but never leaves you once it arrives.

A subtle wake-up call

Chu’s approach extended even to topics most meditation teachers wouldn’t touch. I remember one moment, during a meditation workshop, when he casually handed out a photocopy of a scientific study. The topic? Semen retention.

He didn’t preach. Didn’t moralize. Just smiled and said something like, “Daoists believe managing sexual energy builds vitality. Some science might back it up.”

It wasn’t some dogmatic sermon. It was classic Chu: minimalist, unassuming, quietly provocative. And it stuck with me.

It stuck because it hit a nerve. I was in my mid-30s at the time, coming off more than a decade of globetrotting, and if I’m honest, a pretty wild lifestyle. Always chasing the next high, the next city, the next woman. One-night stands. Parties. Late nights and empty mornings. I thought I was winning at life.

But when Chu mentioned this idea—so casually, with that little smirk of his—it landed like a slap from a wise elder. A quiet wake-up call that made me realize just how much energy I’d been bleeding through that constant chase.

It was the first time I understood that all that chasing was costing me something. That maybe all that outward “freedom” was just inner compulsion in disguise.

And maybe it wasn’t a coincidence that not long after those workshops, I met the woman who would become my wife. That I chose stillness. Family. Fatherhood. Something I never thought I’d want, let alone need.

Chu wasn’t selling abstinence or guilt. He wasn’t pushing purity or shame. He was inviting us to see discipline not as repression, but as redirection.

You don’t have to believe every Daoist legend about immortality through semen retention to get the message:

Don’t let your life force leak in all directions.

Learn to hold it. Contain it. Cultivate it.

In that way, Chu wasn’t just teaching stillness.

He was showing us sovereignty.

Previously in the series → Part 1: Mind control… but in a nice way, Part 2: How two plane crashes led me back to my mind, Part 3: Cockblocked but enlightened.

Coming up in the series:

Nearly a decade later, I found myself in Barcelona—no longer globe-trotting, but still restlessly seeking—when I wandered into a free Transcendental Meditation intro talk. I figured I had nothing to lose. What I didn’t expect was to walk out with a mantra that actually worked… and a growing suspicion that the organization behind it might be just a little bit culty. (Spoiler: it kind of is. But we’ll get to that.)

What did this spark for you? Drop a comment. I read them all.